Giving the City of Homes a Second Chance

“The Comeback City of America,” my friends scoffed. It was 1995, and Springfield was experiencing a wave of violent crime. Drugs and large national gangs, such as Los Solidos, La Familia, and the Latin Kings, established an intimidating presence here. The crack epidemic was devastating neighborhoods. Heroin was selling for about $30 a packet in Springfield back then, while users could buy the same amount in New York City for five dollars. So dealers in the Big Apple and their surrogates in Hartford wanted to cut out the middlemen and came to Springfield to take over the lucrative drug markets, sparking gang wars that led to the city’s peak in violent crime rate: 3,075 violent crimes per 100,000 residents in 1997—twice as high as it was in 2010.

“The Comeback City,” a slogan that seemed ludicrous after the Steiger’s department store downtown closed in 1994, was used ad nauseam in the mayor’s attempts to bring a casino to Springfield and lure the New Britain Red Sox baseball franchise to Springfield that year. It would have been the first minor league baseball team in town since the Springfield Giants left for Waterbury, CT in 1965. Both the casino and the baseball attempts failed.

Above: stylin’ in Steiger’s. Below: the Springfield Giants in Pynchon Park

A half-baked scheme to build a baseball stadium across from the Springfield Newspapers building fell through five years later. Now another casino proposal in the city is currently under consideration from the state. Would a casino bring economic prosperity downtown, particularly to the South End, which was ravaged by a tornado in 2011? Many jaded souls are still skeptical.

The 2011 tornado all but destroyed the South End Community Center, but left its iconic castle-like tower on the right standing.

Above: MGM’s plans for the same area, with the “castle turret” of the South End Community Center—a former armory.

To be sure, I was a little hard on my hometown in When Did Downtown Springfield Jump the Shark? Part 1. So let me make it clear: I’m delighted to be back in the area and working in Springfield, and I’m not afraid to bring my family into the city for dinner or to visit the museums and the Forest Park Zoo. I was a little wary when I first returned, but then I reasoned that you have to watch your step wherever you go, whether it’s Wilbraham or Worcester or Washington, DC, right?

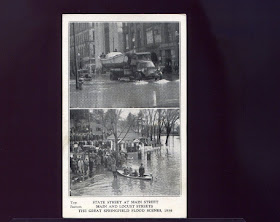

The Comeback City. Springfield has seen up and down cycles throughout its 377-year history. It was burned to the ground by Native Americans in King Phillip’s war in 1675. The great floods of 1936 and 1938 ravaged the North and South Ends, but the neighborhoods came back.

Above and below: the flood of 1936

Its present decline, which some say started when the Defense Department closed the Springfield Armory, America’s first, in 1968, was exacerbated by the relocation of several precision manufacturing companies—the city’s economic base. But Springfield survived. It’s a bit tattered, like Aerosmith and the Rolling Stones, but like those ragged rockers, it has good bones: colleges and universities, arts and culture, popular restaurants and bars, minor league hockey and basketball teams, and the Basketball Hall of Fame. Hopefully the Springfield Falcons will continue to play hockey here after their contracts with the MassMutual Center and the NHL’s Columbus Blue Jackets expire after next season.

When I brought my seven-year-old son to see the Harlem Globetrotters at the MassMutual Center recently, he looked at the “skyscrapers” downtown—the Chestnut Tower, Tower Square, and Monarch Place, and said it reminded him of Boston. My heart swelled with pride. If only he know how fun the city was when I was a kid. It wasn’t exactly Boston, but it wasn’t “Stinkfield” either. (The infamous sewage treatment plant odor didn’t smell up downtown until I was around 15.) It was somewhere in between. Was it a “dying city”? I contemplated this question as Sean and I walked out of the Globetrotters game and down Dwight Street—and I looked at the old Pynchon Plaza, a concrete “pocket park.”

Pynchon Plaza: the view from Dwight Street

Pynchon Plaza was built in 1976-77 as a bicentennial project with state and local money and was a symbol of civic pride. Built on a steep incline to link the museums on Chestnut Street with downtown, it had a waterfall, a reflecting pool, funky sculptures, and an elevator to make the connection to Dwight Street handicap accessible. But one of the sculptures was immediately stolen, and the park was sprayed with graffiti. The hidden corners became makeshift bathrooms, drinking, and drugging spots, and soon the elevator was broken—not that anyone in their right mind used the “rape elevator.” Drunken teens used to jump in the reflecting pool after rock concerts at the Civic Center, and on hot summer days there were confrontations with police when they tried to clear city kids out of the pool and fountain.

In 1981, shortly after a 65-year-old retired patrolman was relieved of his wallet and knocked down the steps of the park, the city turned off the waterfall, drained the pool, and fenced off the litter-filled and piss-smelling park on both sides. It became a symbol of civic failure.

“What’s that?” Sean asked, pointing to the plaza.

“An old park,” I said.

“Not much of a park,” he replied.

“No, it isn’t.”

* * * * * * * *

I remembered walking down the steps of Pynchon Plaza with my friends in high school and a group of men were huddled together drinking there. I wouldn’t say they weren’t homeless, but they were grubby and definitely jobless—hanging out in the middle of the day.

“Hey, man, got a match?” said one. A cigarette dangled from his lips and bounced with every word.

“No,” we said in unison.

“No,” he sneered. “Not for no nigger you don’t.”

“We don’t smoke,” I said with a shrug.

“Yeah, right,” he said, turning to his friends, looking for approval. But they didn’t chime in or even nod in agreement. In fact, they seemed a little disappointed that his friend was trying to intimidate a bunch of kids.

When we got down to Dwight Street, my Dave O’Brien nudged, me pulled a book of matches out of his pocket, and laughed.

“Why didn’t you just give him a match?” I asked.

“Fuck that,” he said. “They would have been asking us for money next. No sense in stopping and getting into some kind of conversation with those guys. Is there?”

He was probably right. Personally, I would have just quickly given him the book of matches and just kept on walking. Was it because they were black that Dave snubbed them? I wondered. Possibly. Unlike me, most of my neighborhood friends went to public schools, and race relations there were awful. These guys had to deal with violence in the schools—and it colored their perspective.

Pynchon Plaza: the view from Chestnut Street as the park was being renovated recently

* * * * * * * *

As my son and walked to the car and talked about the Globetrotters, I took one last look and Pynchon Plaza and saw that it was cleaned up and “open”—that the city had taken down the fence. The mayor held a press conference there in 2010 to celebrate its renovation—even though the elevator still didn’t work, and a fence running right through the middle (right behind the mayor in the photo below) remains a barrier: because of ADA accessibility issues, the park won’t connect to Chestnut Street until the elevator is repaired to the tune of $15,000. So museum patrons still can’t take this shortcut to downtown!

The waterfall was flowing during the press conference (pictured above), but it was dry when Sean and I saw it. Apparently it needs $100,000 in repairs—money the city simply doesn’t have. (Insert sigh here.) Laughably, the city has staged four “re-openings” of this park since it was built. But at least they’re trying to make a go of it again. Because that’s what Springfield does. The little engine that could. I hope it doesn’t run out of steam. Or diesel. Or whatever it’s running on. (Fumes?)

I’ve come to believe think that the condition of Pynchon Plaza is a good barometer of the direction Springfield is heading. Think about it: if the city can’t take care a little park downtown, well…

Below: Pynchon Plaza’s failure has spawned a flurry of ideas from both architectural students and professional architects on what just might work in this critical downtown space. Click on the architects’ names for more info. What do you think? Leave a comment at the bottom of this entry! Personally, I believe that an extension of the Dr. Seuss Memorial Sculpture Garden in the plaza would attract museum patrons, and MGM could help pay for construction since the park would funnel people in the Quadrangle closer to the casino.

UMass Art and Architecture students like the idea of a community center:

* * * * * * * * *

Recalling Dave O’Brien’s comment outside of Pynchon Plaza—complete with the N-word—made me more positive than ever that in order for Springfield to “make it work” these days, it must also come to grips with its troubled racial history: riots that broke out in Winchester Square in 1965 and 1969, and rioting at Technical High School in 1969 and 1971—years before Boston’s busing crisis.

Above and below: allegations of police brutality after the Octagon Lounge riot of 1965.

Above and below: allegations of police brutality after the Octagon Lounge riot of 1965.

Below: the Welfare Office sit-in riot of 1969:

Below: the “Tech Riots” in November of 1969

These racial conflicts were part of the reason the city has experienced dramatic white flight over the years, with its Caucasian population declining 24 percent since 2000. Meanwhile, the number of Hispanics grew by 43 percent in the same time period and now make up 39 percent of the city's 153,060 population. Whites have shrunk to 37 percent of the population, and Springfield is 22 percent black.

These changing demographics have resulted in resentment among many of the remaining whites—bitterness extreme enough for three Sixteen Acres youths to burn down a black church a few hours after Barack Obama’s election victory in 2008.

So you will hear the same thinly veiled racist rhetoric after nearly every murder. You will hear that Springfield is the “was once known as the “City of Homes” because of its beautiful Victorian houses, and now it’s the “City of Homies” after housing deteriorated, homeowners moved out, absentee landlords bought up properties, and “undesirables” moved in.

And every so often I have to stop myself from spouting off—to my friends, or in this blog—whenever a violent crime takes place. Needless to say, it was difficult not to be disgusted when an 11-year-old girl was shot in the leg after someone cut in line in a crowd waiting to buy the new Nike Air Jordans in March of 2013 at the Wal-Mart shopping plaza. I started voicing my doubts about the city—and then held my tongue, because I didn’t want to scare my wife. I know this happened on Boston Road, not downtown. But still.

Again, in terms of violent crime, Springfield is statistically half as rough as it was in 1997. So is Springfield is ready for a rebound, despite its newest nickname—Bangfield? Can this really be The Comeback City? There are reasons to be optimistic: the $78 million renovation of Union Station, which will be completed in 2015, will not only be a nexus for a planned New Haven-Hartford-Springfield Commuter Rail Line, but also for Amtrak’s retooled Vermonter train that will also stop in Holyoke, Northampton, and Greenfield.

Above: the renovation of Union Station began this summer. Below: photos from the Urban Compass blog of the ruins of what was once a grand lobby and what it will look like

As I wrote before: when they build it, will people come—to one of the poorest cities in the state? Welcome to Springfield: home to four colleges and universities and 21 more of them within 15 miles, including several of the country’s most prestigious universities and liberal arts colleges, but more than 26 percent of the city’s population is below the poverty line. Welcome to the city of contrasts. How fucking bipolar.

We’ll see if a downtown casino and a railroad line help bring the city back—the mayor has even announced an “enhanced downtown police deployment strategy.” Until then, I’m sticking to my assertion that downtown Springfield jumped the shark. There, I wrote it again. With that being said, city also jumps back into my good graces from time to time: when I take my family to the post-Thanksgiving giant balloon parade on Main Street I look around, see everyone having a great time, and tell myself that Springfield is indeed getting it together.

I am optimistic enough to predict that in my lifetime I will see Springfield go from “jumped shark” to Hot Tuna. But I repeat: as I wrote in Part 1, until I see and hear rock bands of the caliber of Hot Tuna downtown again, Springfield isn’t exactly shark city to me, but, sorry Charlie, it’s no Hot Tuna. It’s lukewarm flounder at best. Maybe, with the proposed casino—and the casino developers promising to bring concerts back to the Paramount Theater/Hippodrome and the MassMutual Center—things will be heating up soon.

I know that I must effectively deal with my mixed feelings about my old city. It’s both exciting and depressing to drive on its streets, mined with potholes and lined with abandoned buildings, and see my youth flashing—and fading—before my eyes. Springfield: so full of promise and despair. One city, two ends of the spectrum, and a fleeing middle class. I guess I can accept Springfield’s dichotomy and hope for the best. Despite all the shootings lately, I’m still giving Springfield another shot. (I wonder if the police’s ShotSpotter gunfire-detection system was activated with that shot.)

I’ll mention a homily given last year by Father Joseph Serrano, pastor of St. Cecilia Church in Wilbraham. He wasn’t talking about Springfield, but nonetheless I can apply his talk to the city’s future. Describing one of Jesus’ parables, Luke told the story of a man whose fig tree didn’t bear fruit for three years and ordered the worker who took care of it to get rid of the barren tree. “Leave it alone for one more year,” the keeper of the vineyard begged. “I will dig around and put fertilizer on it. If it has fruit next year, fine. If not, then cut it down.”

As the keeper of the vineyard gave the tree a second chance, I’m giving Springfield another try, especially because it’s not totally barren yet. I’m convinced that I can let Springfield back into my heart. Like Alfred Kazin writing about his youth in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn—he had to leave Brooklyn in order to truly appreciate it—I am back, and I am ready to embrace it.

And I must admit that my embrace with Springfield isn’t an all-enveloping bear-hug. Since I don’t actually live there, it’s more like the lame-ass hug (chest in; hips/ass out) described in that Seinfeld episode. But I must acknowledge that the city, like my parents and friends, helped make me who I am, for better or for worse.

And my patching things up with Springfield isn’t unconditional. If I get mugged there, the deal is off. After all, the literal translation of the Fig Tree keeper’s request is, “Leave it alone for one more year. I will dig around and dung it.” So be good to me, Springfield, or I’ll shit all over you—even more than I already have in this blog.

cE9s4Ptn,yBQiN95rh-Q~~60_3.JPG)