Youngsters show where they found human bones in what is now known as North Branch Tributary Park.

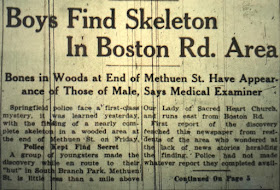

A handful of kids cutting through some woods in on a Springfield’s Boston Road neighborhood in 1951 soon discovered that it wasn’t going to be their average November day.

Twelve-year-old Walter Gibbs was 50 feet in the woods at the end of Methuen Street with a couple of neighborhood friends on November 23 when he spied a round object nestled against a tree. A human skull! Gibbs, who lived in nearby Newfield Road, was with Frederick Traggio, 12, of Glenwood Boulevard, and 10-year-old Pasquale Covelio.

So Gibbs did what a kid might do—act before thinking—and carried the skull out of the woods at the end of a stick. Imagine the reaction of their friend John Dick, of 166 Methuen Street (next to the woods), when he walked up and saw Gibbs displaying his find. Dick told his friends that they should call the police, which they did.

Skull on a stick, anyone?

But before police got there, Gibbs and company again did what kids might do in such a situation—contaminating the scene by combing through the forest floor looking for more bones. They found them, including the lower part of the jaw, and a kneecap about 50 feet away. The police finally found a thigh bone, skull, some ribs, the pelvis, and other bones—about two-thirds of the bones of a male skeleton were ultimately discovered. Police hoped that because some teeth were attached to the skull they might be able to make an identification.

Police also removed from the scene a tube of lipstick, a couple of old newspapers, and a perfume bottle. The bones “were partially covered, although as nature might have lifted leaves or light debris over parts of them,” according to the Springfield Union newspaper. The city’s medical examiner, W.A.R. Chapin, said the remains had apparently not been buried, but had sunk into the dirt—some of them lightly covered by grass, leaves, and rotting debris. He had theorized that heavy rain that Friday may have washed them to the surface. Police thought that “the bones probably not been there since the death of the victim” because of the presence of fill along the road. The fill, according to the kids, had been there for only a few years, and the bones “in some cases were atop it.”

There were no marks indicating that the deceased was wounded with an instrument, although the children said the skull had a hole in it. “This might have occurred through the action of the weather over a period of years,” according to the story, although the author didn’t attribute this “hole” theory to anyone. The account wasn’t published until three days after the gruesome discovery, when residents contacted the newspaper wondering why it hadn’t been reported. Police explained the delay was because they hadn’t completed their report. At the scene, one of the boys had suggesting contacting the newspapers, hoping to get his photo in the paper. Police told him not to “because we don’t want a lot of questions before we know what happened.”

The pin above marks the approximate spot where the boys found the remains. Methuen Street is divided in two by the woods—the discovery was made at the dead end of the longer section of Methuen Street (the one that intersects with Boston Road). The two houses at the end of Methuen are from the early 1920s, so the location of the dead end remains the same—the immediate adjacent wooded area has remained undeveloped.

According to the newspaper story, the boys had originally walked into the woods en route to their “hut” in South Branch Park. I believe the author had meant North Branch Park, because South Branch Park is more than a two-mile walk away. As I imagine the scenario of this adventure—right out of Stephen King’s Stand by Me—it’s difficult for me to fathom that these “boys” are now over 80 years old, or approaching 80, and one or more might be as dead as the skeleton they found.

The bones were taken to the School of Legal Medicine at Harvard University, where pathologists worked on recreating the structure of the skeleton. The skull had a fairly complete set of upper and lower dentures, so police were confident the identity could be found.

Investigators immediately started dusting off missing persons reports from decades prior. There was speculation that the remains could be that of Samuel Manzi or Alexander Tekla (AKA Alexander TAKLA and Aleck the Syrian), who disappeared in 1931 and 1934, respectively. They both had several arrests, including a Manzi arrest for selling liquor in 1928, during Prohibition. Manzi, who lived in the South End, and Takla might have been fringe players—or more—in organized crime and were believed to have been 'taken for rides.'”

The names Manzi and Takla were invoked several times in the coming years whenever bones were found in area woods. In October of 1931, a skeleton was found in an East Longmeadow swamp, and the police thought could very well be Manzi.

But it turned out that it was 61-year-old John Robinson, a “Negro” identified by relatives because they recognized his shoes, twine shoelaces, and a patch that had been sewn onto the left leg of his pants.

In December of 1932, a skeleton was found in some East Longmeadow woods and police initially thought it was Manzi, but it was someone else. In April of 1933 a skeleton was found in a building contractor in Wilbraham and police wondered if it were Manzi’s. However, it was thought the remains were probably from an old cemetery next to the construction site. The Warner family burial plot graves had been moved to another cemetery years ago, and they might have missed a body in the exhumations.

In 1934, Takla’s brother contacted district attorney Thomas Moriarty about Alex’s disappearance, but Moriarty downplayed it, saying they police “were not interesting themselves in the whereabouts of Takla, who is known to the department,” and figured he show up some time. He didn’t.

In 1935, when some bones were found in a shallow grave behind a roadside vegetable store on Riverdale Street in West Springfield, police initially thought the remains might be either man, but they weren’t.

The case of Sam Manzi was brought up in a 1947 newspaper story about unsolved murders. It was “not listed as a murder because no trace of him was ever found. Officers who handled the investigation, and Manzi’s relatives, thought that he was “taken for a ride.”

After that, Manzi and Takla were forgotten about in the media until 1951. Could either of these Springfield men have been brought to the woods off Methuen Street—either in a car as a “passenger” or in a truck scooped up with earthen fill from another area?

Stay tuned for Part 2!